The Uncertain Mind: How the Brain Handles the Unknown

Our brain is wired to reduce uncertainty. The unknown is synonymous with threats that pose risks to our survival. The more we know, the more we can make accurate predictions and shape our future. The path forward feels more dangerous when we can sense essential gaps in our knowledge.

In fact, fear of the unknown has been theorized to be the “one fear to rule them all”—the fear that gives rises to all other fears. Unfamiliar spaces and potential blind spots make us uncomfortable. This fear makes sense from an evolutionary perspective, but can be unnecessarily nerve-wracking—and sometimes paralyzing—in our modern world.

Fortunately, we have also evolved an ability that’s deeply human: metacognition, or thinking about thinking. Metacognitive strategies can help us think better and manage the anxiety that arises from the unknown.

How the brain reacts to uncertainty

Humans react strongly to uncertainty. A study from researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison shows that uncertainty disrupts many of automatic cognitive processes that govern routine action. To ensure our survival, we become hypervigilant to potential threats. And this heightened state of worry creates conflict in the brain.

First, uncertainty impacts our attention. The sense of threat degrades our ability to focus. When we feel uncertain about the future, doubt takes over our mind, making it difficult to think about anything else. Our mind is scattered and distracted. We feel like we’re all over the place.

The underlying biology is still poorly understood, but research in primates conducted by Dr Jacqueline Gottlieb and her team at Columbia University’s Zuckerman Institute reveals that uncertainty leads to major shifts in brain activity, both at the micro-level of individual cells and at the macro-level of signals sent across the brain. Put simply, their results suggest that our brain redirects its energy towards resolving uncertainty, at the expense of other cognitive tasks.

Uncertainty also affects our working memory. You can think of your working memory as a mental scratch space where you jot down temporary information. Working memory is attention’s best buddy. It’s what helps you visualize the route to a new place when you drive and keep several ideas in as you write down a sentence.

Our working memory capacity is limited. Cognitive load is the amount of working memory resources we use at one given time. A high cognitive load means that we’re using a lot of our working memory resources. And uncertain situations force us to use additional working memory resources.

In the words of Samuli Laato, a researcher at the University of Turku: “Uncertainty always increases cognitive load. Stressors such as health threat, fear of unemployment and fear of consumer market disruptions all [cause] cognitive load.”

Cognitive overload makes it harder to keep crucial information in mind when making decisions or to think creatively by connecting ideas together when we experience. Because it has such a big impact on our cognitive functioning—decreasing our attention and using up more of our working memory resources—uncertainty often leads to anxiety and overwhelm.

The good news is: the heavy load of uncertainty is not inevitable. Studies suggest that responding to uncertainty is resource-intensive, but metacognitive strategies can help us reduce the impact of uncertainty.

By using thinking tools, we can offload some of the burden uncertainty puts on our mind, so we can regain control of our attention and free our working memory resources—and, ultimately, think more clearly in times of uncertainty.

A thinking tool for dealing with uncertainty

Uncertainty is not a binary concept—“I am certain or I am uncertain.” Rather, uncertainty is multifaceted, with many flavors that should be treated differently.

Former United States Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld famously said: “…there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”

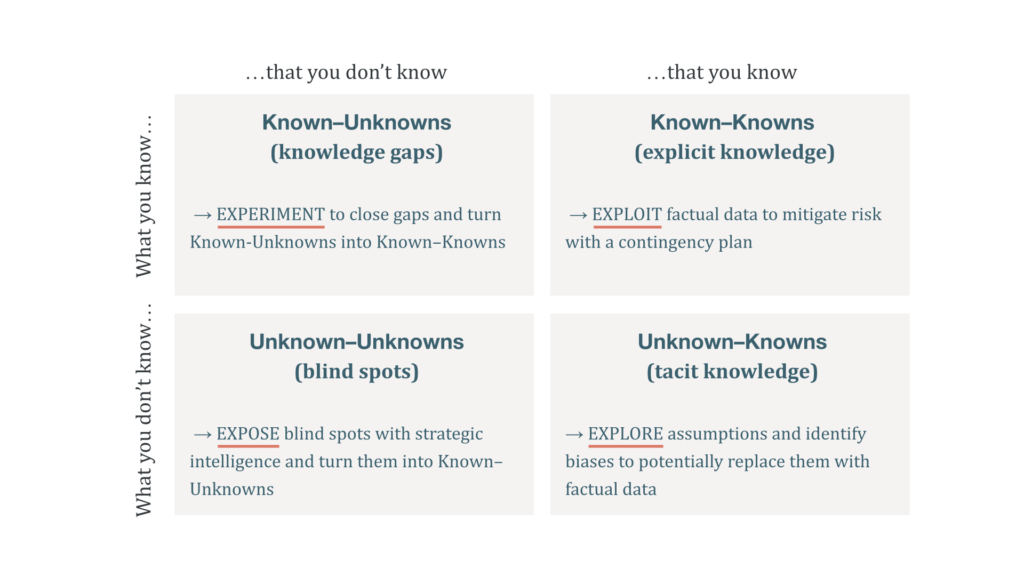

The Uncertainty Matrix, sometimes called the Rumsfeld Matrix, is a tool that can be used to help make decisions when facing an uncertain situation. It can be used to differentiate between different types of uncertainties, and to come up with possible solutions for each.

The matrix consists of four quadrants: Known-Knowns, Known-Unknowns, Unknown-Knowns, and Unknowns-Unknowns. Each quadrant represents a different type of uncertainty, and each has its own set of possible solutions.

- Known-Knowns are uncertainties that are known to us, and that we can plan for. For example, if we know that there is a high possibility of a layoff at our company, we can make a plan for how to deal with it.

- Known-Unknowns are uncertainties that we know exist, but where we don’t have enough knowledge to make a plan. For example, we may not know if our company will be acquired by another in the future. Or, you may be aware of the inherent uncertainties of leaving your job to work on a venture of your own, but you can’t make a step-by-step plan of what to do because you don’t have enough data yet.

- Unknown-Knowns are uncertainties that we’re not aware of but that we tacitly understand, which may lead to biases and assumptions in our decisions. Hidden facts.

- Unknowns-Unknowns are uncertainties that we don’t know about. For example, a new technology may be developed that makes our product obsolete. “ unknown unknowns are risks that come from situations that are so unexpected that they would not be considered.”

Once we know what type of uncertainty we’re dealing with, we can come up with possible solutions.

For example, if we’re dealing with a Known-Known, we can exploit the factual data at our disposal to make a contingency plan, which will allow us to mitigate known risks.

When dealing with a Known-Unknown, we conduct experiments to gather more information, so we can close some of our knowledge gaps and turn those Known-Unknown into Known–Knowns.

For Unknown-Knowns, explore our assumptions—the things we don’t know we know—and identify biases in those assumptions, so we can potentially replace them with factual data.

Finally, in the case of Unknown-Unknowns, we can conduct market research and use strategic intelligence to try and uncover blind spots. It’s a good practice to have in place, but it should be noted that there is no guarantee we will be able to turn Unknown-Unknowns into Known-Unknowns. There will always be events we could not have predicted.

The Uncertainty Matrix is a useful tool for dealing with uncertainty, and can help us make better decisions when faced with it. It’s even better when used as part of a team, as different people may have different perspectives on the same uncertainties.

“The oldest and strongest emotion of humankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown,” wrote H.P. Lovecraft.

While the fear of the unknown is deeply rooted in our biology, it is possible to elevate ourselves above our automatic reactions so we can make the most of uncertainty. Metacognition can be a great ally in reducing anxiety, freeing our working memory resources, and making better decisions when navigating unfamiliar spaces.

https://nesslabs.com/uncertain-mind